A whole year hiatus: isn’t that what shmittah, the sabbatical year that the Land takes religiously, hunkering down under a thick blanket of weeds with a big “do not disturb” sign stubbornly barring you from coming in to clean things up, is all about? It took a lot of willpower for farmers in Israel to stand outside of that closed door, pruning shears in hand, counting down to Rosh HaShana and the first opportunity to barge in and tackle a year’s worth of tasks. In short: there was nothing to write about except our impatience, and no one wants to read about that.

And barge in we did, with a fury. There is SO much to take on after a lengthy period of sitting on your hands, it’s hard to keep track. Disorder is the farmer’s enemy, and it’s nice to breathe again and get down to work. Here is a rundown of what’s been happening over the past month, ever since the new year has freed us to work the land once again.

Ira did a massive, down to the very bare-bones pruning of the olive trees before shmittah. Because we did not interfere at all this past year, the chazirim (suckers) pretty much swallowed up the trees and sucked nutrients away from the three main branches. So as soon as we could, we got to work on cutting the shoots down. Hopefully the rainy season will rejuvenate the trees. (We’re not doing a masik [oil press] this year, because heavily-pruned trees take a few years to regain their strength, and the oil from this year’s press would be kedushat shevi’it oil, making it very difficult to handle from a kashrut perspective.)

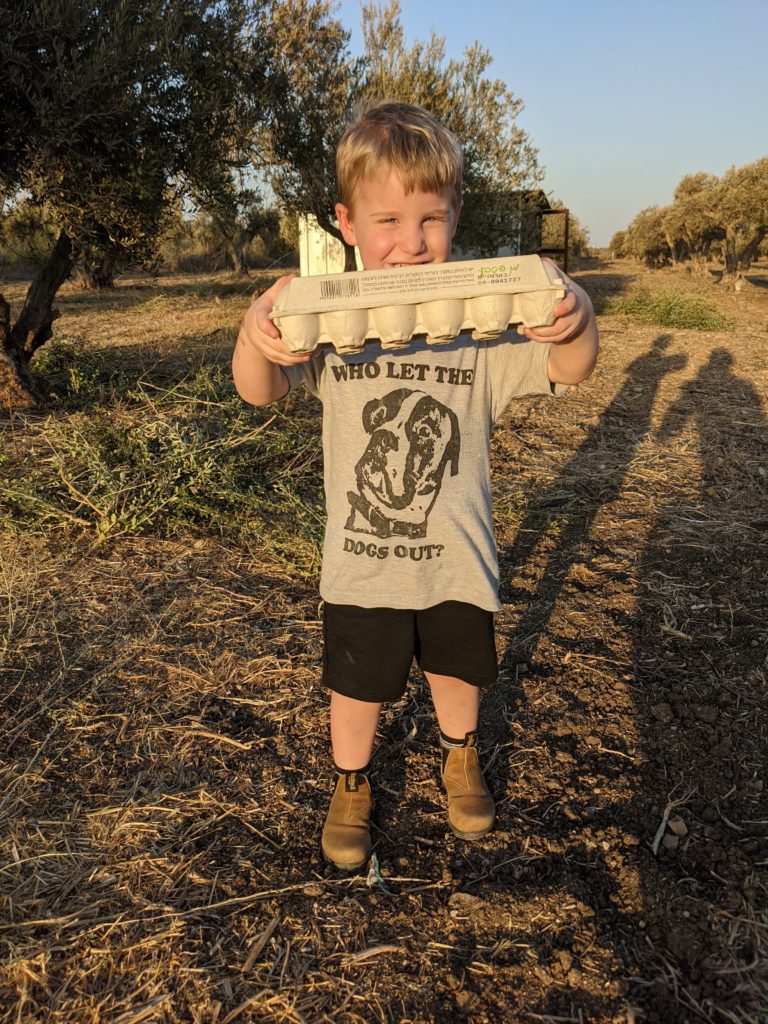

What started as a very modest flock has boomed into over two hundred fowl. The flock grows exponentially, and we’ve added some dogs to make sure that mongoose and other predators keep a wide berth. We’re regularly consuming all of this free-range goodness. Tonight’s Shabbat dinner, for instance, is turkey meatballs (made with our turkey and eggs), and soup made with stock from our chickens.

This year, we’ve sown over the field and planted tiltan (clover). Clover is nitrogen-fixing, meaning it draws atmospheric nitrogen into the roots. There’s no need for fertilizer or pesticides. This will hopefully help the earth regenerate and build up a thicker humus (not the stuff you sop up with a pita, but the term for the verdant top layer of soil that’s thick with nutrients from carbon decay).

Foraging is fun, but competitive, especially up here where many people are competing for the same resources. So Ira harvested wild blackberries and asparagus seeds to germinate. We’re hoping to bring some of that wild goodness into our garden as more luscious food sources. Why forage when you can grow yourself?

Now for Ira’s latest baby, the black soldier fly larvae system. What follows probably needs a trigger warning for “yuck.” I remember sitting in Paul Rozin’s Psych 101 class in Penn (way to go, core curriculum!) when he lectured on disgust, his speciality. He showed a video of a dead cockroach being slowly dragged along a plate of mashed potatoes. He then showed a video of a live cockroach scampering on top of the same plate. Both are gross, as is the subject of these next few paragraphs: Black Soldier Fly Larvae and You.

This past month, Ira has been delving deep into the dark world of breeding black soldier flies. Anyone who lives in Sde Ilan, or has visited, would wonder why he seems to be bringing coals to Newcastle. Our moshav has a real fly problem, since most of the farms raise dairy or beef cows in confinement and the manure piles are prime fly breeding grounds. Why introduce more flies?

Well, you clearly haven’t met the wonderful critters called Black Soldier Flies. First of all, as larvae, they make the most nutritious, free, high-quality feed for all of our poultry. Secondly, the growing larvae plow through all of our kitchen scraps, transforming all of that organic matter into quality feed. It’s an efficient system that solves problems and produces free solutions: highest quality nutrient dense free chicken feed, and efficient use of kitchen waste. Thirdly, there’s the strange and wonderful benefit to us that the larvae busily munching on the organic waste repel those nasty flies that are the bane of our existence (scientists aren’t sure why — they think it might have something to do with a smell, undetectable by humans, that the larvae might be emitting). Fourthly, the black soldier flies drawn to the kitchen scraps are averse to humans, and aren’t vectors for disease. They live only 3-5 days as “adult flies,” and as flies they don’t eat food, only drink water.

This is how it works: adult black solider flies are attracted to the smell of organic waste. They lay their eggs on or above the waste, inside of a box that we are regularly filling with our kitchen scraps.

The eggs hatch in a few days into a couple thousand baby larvae. the larvae grow extremely rapidly over the next few weeks, eating approximately double their weight daily. At that point, they have a natural instinct to climb out of the waste to find a nice patch to pupate (which means to burrow themselves into dirt, where they’ll metamorphise into flies). But no! We have hungry chickens to feed. So instead, Ira’s taken advantage of their climbing instinct, and built a ramp in the bin which empties into a bucket.

And into that bucket fall all of the mature larvae, ready to be carted over to the chickens. Isn’t that a wonderfully efficient and elegant use of resources?

Finally, we’re waiting on the ishurim (permits) for the large aquaponics greenhouse (for more on aquaponics, read this older post.) Ira had built a small, experimental version years ago to work out the kinks, but now it’s time to scale up. (And P.S, the BSF larvae also make the perfect fish food for that system!) Once we get it up and running, it’ll be time for another blog post!