It is the life we want, no more and no less than that, our own life feeding on our own vital sources, in the fields and under the skies of our Homeland, a life based on our own physical and mental labors; we want vital energy and spiritual richness from this living source. We come to our Homeland in order to be planted in our natural soil from which we have been uprooted, to strike our roots deep into its life-giving substances and to stretch out our branches in the sustaining and creating air and sunlight of the Homeland. Other peoples can manage to live in any fashion, in the homelands from which they have never been uprooted, but we must first learn to know the soil and ready it for our transplantation. We must study the climate in which we are to grow and produce. We, who have been torn away from nature, who have lost the savor of natural living — if we desire life, we must establish a new relationship with nature; we must open a new account with it. (A.D. Gordon, Our Tasks Ahead [1920])

When I learn, I like to savor the text. I read it, and then let it sit there for a few moments, hanging, potent and delectable, before I start dissecting the language and thinking deeply about the subtleties and implications. I try to allow for a pregnant pause when teaching, as well, so that others can share in that brief silence — I see them first reeling from the initial impact, then marveling over the concept. What a joy to watch others’ joy! It is always the text that delivers — entirely on its own, with only some short explanatory words tossed in here and there — and it is my greatest happiness to share such beauty with others.

Recently, I’ve been seeking out new texts. The selection above, for instance, from “secular prophet” Aaron David Gordon — that one required some time and quiet space for me to feel its full weight. It lacks the power of a biblical or midrashic passage, to be certain, but its relevance to both a period of history that I’ve come to deeply admire, as well as its current application to my personal life, have me gobsmacked.

When I guide, I let the land talk to me. It always has what to say, and I’m happy to listen, so that I have something to share with the people who have come to experience the land along with me. I make sure to give pause and proper silence then, too, so that others can take in the encounter on their terms. The land speaks with its perfect, nuanced language to each one of us separately. If we listen carefully enough, everyone understands what it is trying to say, each of us in our own way. I must take care, in teaching and in guiding, to let the text and the land speak for themselves, so that each person can develop and nurture his own unique relationship with what he is studying or the region he is encountering.

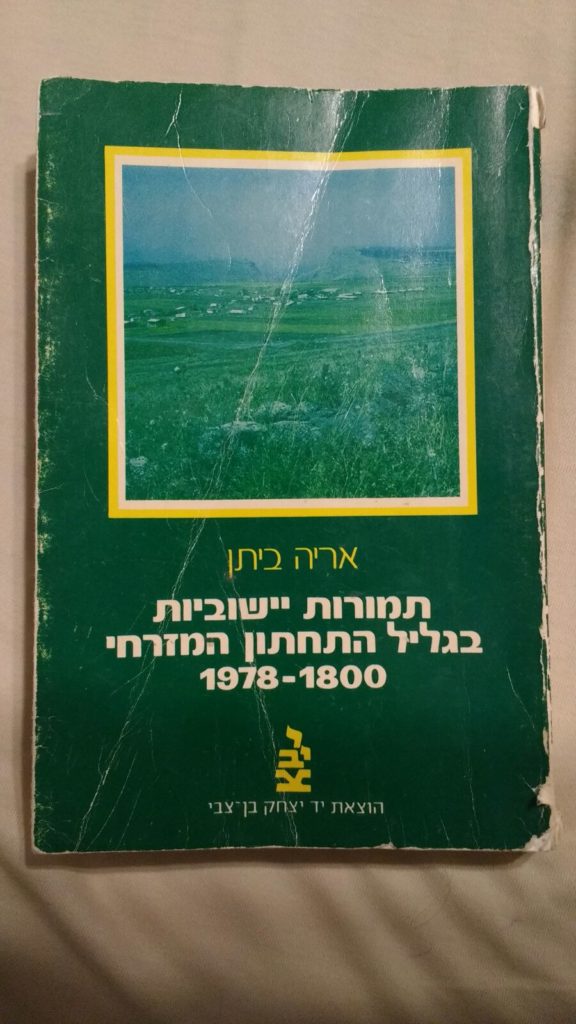

Recently, I’ve been looking at the land differently. My focus had always been archaeology, particularly the interplay of Bible and Land, as well as Second-Temple history and Land. Of late I’ve been devouring memoirs of the early zionists, principally of the fiery Second Aliyah period, and their modern contribution to our land, and analyses of soil and weather conditions in the north. This, for instance, is my riveting nightstand read (I’m not being facetious; it’s really fascinating):

Torah and Eretz Yisrael, Eretz Yisrael v’Torah…תורת הארץ. The two are so deeply intertwined in my experience, though exposure to one began well before the other. Those formative years of Torah study were the ציונים בדרך, the signposts to a destination that I’d never visited. There was much I thought I understood, and much more that I knew I did not — age and circumstance hadn’t yet granted me sufficient exposure, training, maturity, patience or caution. (They still haven’t, in some aspects.) But making Israel my home planted me in the resting-place that those signposts all point to, clearing away much of the misunderstanding, steadily nurturing my desire to draw deeper and deeper from that מעיין נובע that is תורת ארץ ישראל.

What exactly is Torat Eretz Yisrael? Is it Torah taught in the Land of Israel, or Talmud Torah developed by scholars who are native to Israel? Perhaps it is something else entirely: an interweaving of text and land, where knowing the Land helps me know the Torah, and knowing the Torah helps me know the Land. Maybe only a deep, elemental knowledge of living on and in Eretz Yisrael — that easy and organic understanding of place that we associate with “being at home” — affords someone the opportunity to understand the Torah, and have a profound relationship with the Torah, in the most intimate of ways.

Decades back, we began our love story with this land, and now are starting a new chapter in our story, one that will be written in chicken coops and aquaponic hothouses, in boots dirty with manure and arms aching from olive harvest — and where the day-to-day will involve separating trumot and ma’asrot, the intricacies of the halachot of shmittah, the very real applications of pe’ah and ma’aser beheima.

…החקלאות, הלא היא אצל כל העמים רק גורם כלכלי חיוני פשוט. אבל העם אשר הנושא שלו כולו הוא קודש קדשים, וארצו ושפתו וכל ערכיו כולם קודש הם… – הרי גם חקלאותו כולה היא ספוגת קודש. (מאמרי הראי”ה ח”א עמ’ 179-181)

Agriculture is nothing more than an essential economic agent among the peoples of the world. But for the nation whose every aspect is the Holy of Holies, and its land and language, and all of its values, are all holy…, then even its agriculture is saturated with holiness.

I cannot help but feel that this next chapter must be one that will deepen our intuitive understanding of the Torah. It is one thing to be able to confidently speak of the nature of the places where our Avot lived, where the tribes settled and the events of the Torah and Jewish history played out. It is another to have firsthand, immediate knowledge of kedushat Eretz Yisrael as expressed through sustained exposure to mitzvot hateluyot ba’aretz (agrarian-based mitzvot).

The years I’ve been engaged in Talmud Torat Eretz Yisrael — learning, teaching, guiding, writing — have been filled with contemplative pauses, so that I can take in the full impact of what needs to be absorbed. Now it’s time to fill this new chapter with fresh texts to pour over and let steep.

Come sit with this poem by R’ Kook for a while, and afterwards let us talk of תורת ארץ ישראל:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3QmmTqtmzLc

Existence, whisper to me a secret!

“I have life — please partake —

“If you have a heart beating blood, not yet polluted by the poison of despair.

“But if your heart is closed,” whispers Existence to me,

“And my beauty doesn’t enrapture you,

Then turn away from me — I am forbidden to you.

“If every delicate chirp, all living beauty

Doesn’t inspire a holy song, but instead rouses within you a foreign fire

Turn well away from me, since I am forbidden to you.

A generation will rise

And will sing for beauty, and for life, and for endless renewal,

Nursed from the dew of heaven…

From the glory of the Carmel and the Sharon

The living nation will listen to the manifold secrets of Existence

And the delicate song and gorgeousness of life will be filled with a holy light

And Existence will be drawn to say:

My chosen ones, to you I am permitted!

(With special thanks to R’ Yosef Bronstein)