I was a heavy eight months pregnant with our seventh child when we first met with Geveret (Mrs.) Reich at her nahala in Sde Ilan. I couldn’t walk much at that point, but never mind — had I been a spry college student overseas for a kibbutz adventure, I probably wouldn’t have been able to keep up with this octogenarian. Chana Reich is a slight woman, but her delicate stature belies an imposing stamina and a formidable will.

As Chana strode through her property in the heat of July, it seemed as though the years themselves were melting away. She had lived in Sde Ilan for upwards of half a century — she had seen the history that I cherish so deeply and am insatiably curious about unfold at a breathtaking pace. She proudly showed the details of her life’s work to Ira, while I hung back and took it all in.

(Ira later pointed out the absolute pleasure of listening to an old-time professional Hebrew teacher speak Hebrew — have you ever noticed how measured the pace of their enunciation is, how exacting the pronunciation, how sparingly and simply they communicate? It’s like butter. A S.Y. Agnon story read aloud. Worlds apart from the furious velocity of modern Hebrew, where I will always have to ask for the speaker to repeat himself, never quite catching his meaning the first time ‘round.)

After they toured the property, we all sat down in the dusty kitchen of the home she hasn’t lived in for a decade to talk about who we were, and who they were. Chana Tzippora Yaffe and Yaakov Reich met in the early 50’s at the newly-established moshav of Sde Ilan (established in 1949). She was a Hebrew teacher, recruited by the Ministry of Education to move from Jerusalem to the periphery where they were in desperate need of educators (she randomly chose Sde Ilan from a list, as she liked the name). There she met Yaakov, one of the six Reich boys who had moved with their parents from Haifa to Sde Ilan in the “From the City to the Village” campaign.

The Reichs were Hungarian survivors of the Holocaust who arrived in Palestine from Budapest shortly after the war. Yaakov and Chana raised four children in their nahala, two girls and two boys, none of whom stayed on as moshavniks. After Yaakov passed away, Chana went to live with one of her sons in Tel Aviv.

Why does any of this matter to us? It’s not like we cared much about the family history of the couple from whom we purchased our house in Maale Adumim nine years ago — nor did I take more than a polite interest in the stories of any of the other homes that we have lived in. The difference lies in what this move means to us, what owning a nahala means:

ההבדל בין הקנאה ונחלה הוא עצום. המקנה מעביר, אמנם, את החפץ לרשותו של הקונה, אבל העברת רשות זו אינה יוצרת שום יחס אישי ושום קשר פנימי בין המקנה והקונה. מה שאין כן בהנחלה. המנחיל מעמיד את הנוחל תחתיו. והנוחל קם תחתיו של המנחיל. ומתוך כך ההנחלה יוצרת יחס פנימי בין המנחיל והנוחל.

The difference between a kinyan (purchase) and a nahala (legacy) is vast. A seller transfers the object to the possession of the buyer, but such a transfer does not create a personal relationship or internal bond between the seller and buyer. This is not true of a nahala. There, the benefactor appoints the beneficiary in his stead, and the beneficiary assumes the status of his benefactor. Thus, a nahala forges an intimate relationship between benefactor and beneficiary.

— R’ Yitzchak Hutner, Pachad Yitzchak (Shavuot), 16:10

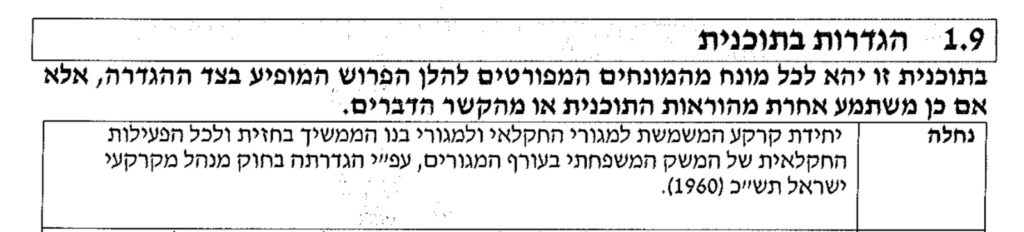

The fact that we did not inherit this land, but bought it — and the fact that “nahala” as an Israeli legal term refers narrowly to a plot of agricultural land with residences for the farmer and his children, and not more broadly as R’ Hutner had intended it — changes nothing in the acute relevance of this passage from the Pachad Yitzchak. This land is both technically a nahala and is, far more profoundly, a legacy. We have been entrusted by the family that had originally tended this land to care for the field that will outlive us, and which we can never truly own, any more than they ever owned it.

The Reich’s relationship to the nahala that they built with the sweat and grit of real chalutzim (pioneers) — “you should have seen Yaakov and me, days and days with a wagon, clearing off the stones from the land so that it could be tilled!” — is a critical chapter in the story of this particular area of Eretz Yisrael, this specific place whose character has been formed through the ages by Yael, by Barak, by the tribe of Naphtali, by the Tannaim and the Crusaders and Salakh-a-din and Manya Shochat and David Gruen (later known as Ben-Gurion). There is much to tell of what this specific tract of land has witnessed, and much to dream about what will be with this nahala in the eager yet inexperienced hands of its new caretakers.

What buying a nahala really means is continuing a relationship with the land — through this, we realize the intimate personal relationship between those that have come before, and those that shall come after. Our dreams are Chana’s dreams — “I am giving the responsibility now to you — if you weren’t you, if I hadn’t met you and been reassured that you cared as deeply as I do about this land, that then we wouldn’t have a deal!”

The morning that we signed the contract, Ira and I went to Kever Rachel. Rachel Imeinu is most accessible to us — and since we are moving to her Naphtali’s nahala (tribal territory), we started our day speaking to God and thinking of Rachel. Is your throat still choked, Rachel Imeinu? The Reichs have cleared your son’s nahala from all of those stones and planted gorgeous olive trees, and now we will tend those trees and plant more trees, and learn and teach about being deeply rooted, no longer on the way, as you always were. Here we are, Rachel Imeinu — dry your eyes, come and collect eggs with us and laugh at the kids’ musical.ly videos about life with sheep and cabbages and chickens. Be rooted, finally — יש תקוה לאחריתך. Hashem, bless Your Land, bless those who are passionate about your Land, bless the faithful who observe the mitzvot You granted to those who tend Your Land. With this, we set out for Tel Aviv, where Chana Reich was waiting for us.

Next installment: When Your Mispar Zehut is Six Digits, plus How to Buy a Nahala